How to connect with nature through art

In a life I didn’t live, I would have gone to art school.

At school, we were strongly encouraged to take the traditional routes of Oxbridge education, studying English or Law or Mathematics. Art was viewed mostly as a hobby - an exercise in free expression to be done outside of hours, before getting back to the real, more important world of training to be a middle manager in a faceless corporation.

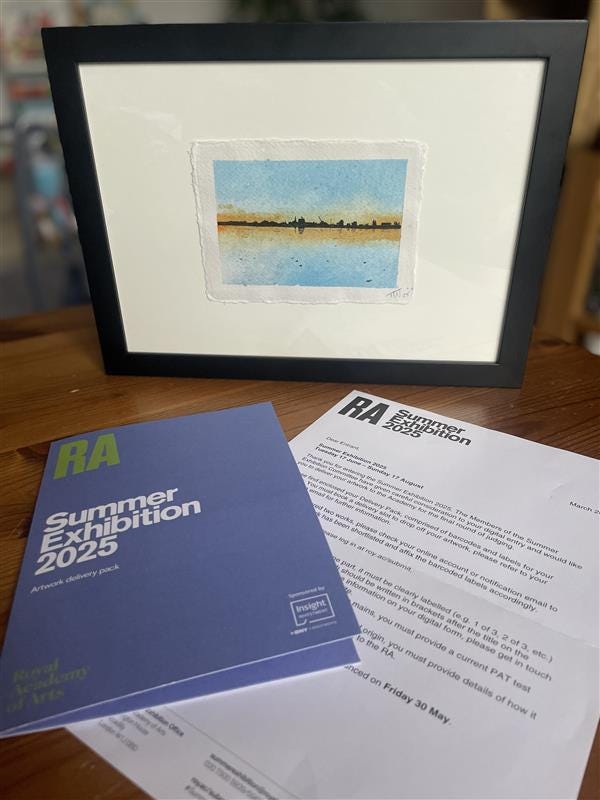

I’ve always loved drawing but found I could express myself better in other ways - through writing, photography, film, and screaming in the middle of a field. So it was thrilling for a small watercolour I painted of Walthamstow Wetlands to be shortlisted for the Royal Academy of Art’s Summer Exhibition this year.

I was instructed to package it up and take it to the Royal Academy in London where it was to be judged. The atmosphere was fabulous. People carried enormous canvases on their shoulders, wheeled them in carts and unloaded them from vans. TV crews interviewed artists who had travelled internationally to bring their work to the RA. They wanted to know what they created, why they created, and what inspired them.

Ultimately, my little painting wasn’t chosen to be exhibited. But the process of being shortlisted suggests that what inspired me - a quiet sundown over a reservoir of coots and swans and cormorants - also triggered something in somebody else.

Nature is at the core of what I do. Looking back on the formative moments of my life, the commonality with all of them is some kind of connection with nature.

There’s something about creating art - especially the tactility of putting pencil or paint to paper to canvas - that helps people process an experience. In the same way an author could gush for pages on how they remember the evening light playing on the water of their childhood, or the sounds of a British bramble thicket in Spring, an artist can convey the same emotions with brushstrokes. It’s not so much a method of communication but of expression, of capturing a mood and a place and a memory.

There’s an imperfection to practical painting that scratches an itch that a perfect image wouldn’t necessarily be able to.

Today, AI generators can spit out perfect images in seconds. But there’s rarely a story to be told there. They might be pretty enough portraits, but by their very nature are simply amalgamated from every other wildlife portrait that exists on the internet - making them about as generic as it is possible to be.

Perhaps it’s this flawlessness - this ability for machines to churn out glossy pictures without breaking a sweat - that makes me seek out the beautifully imperfect work of human artists.

The Wildlife Photographer of the Year Awards, exhibited each year in London’s Natural History Museum, are a necessary annual pilgrimage for me. Each photograph is exquisitely composed and presented. But the ones that speak to me personally are the entries in the photojournalism category, which tell the remarkable stories of the intersection of human and natural worlds. There’s an unflinching honesty to them, and many that bring me to tears.

These photos would have been impossible to stage or replicate with the same effect. I recently came across the mesmerising journals of David Measures that glow with a similar honesty.

From his obituary:

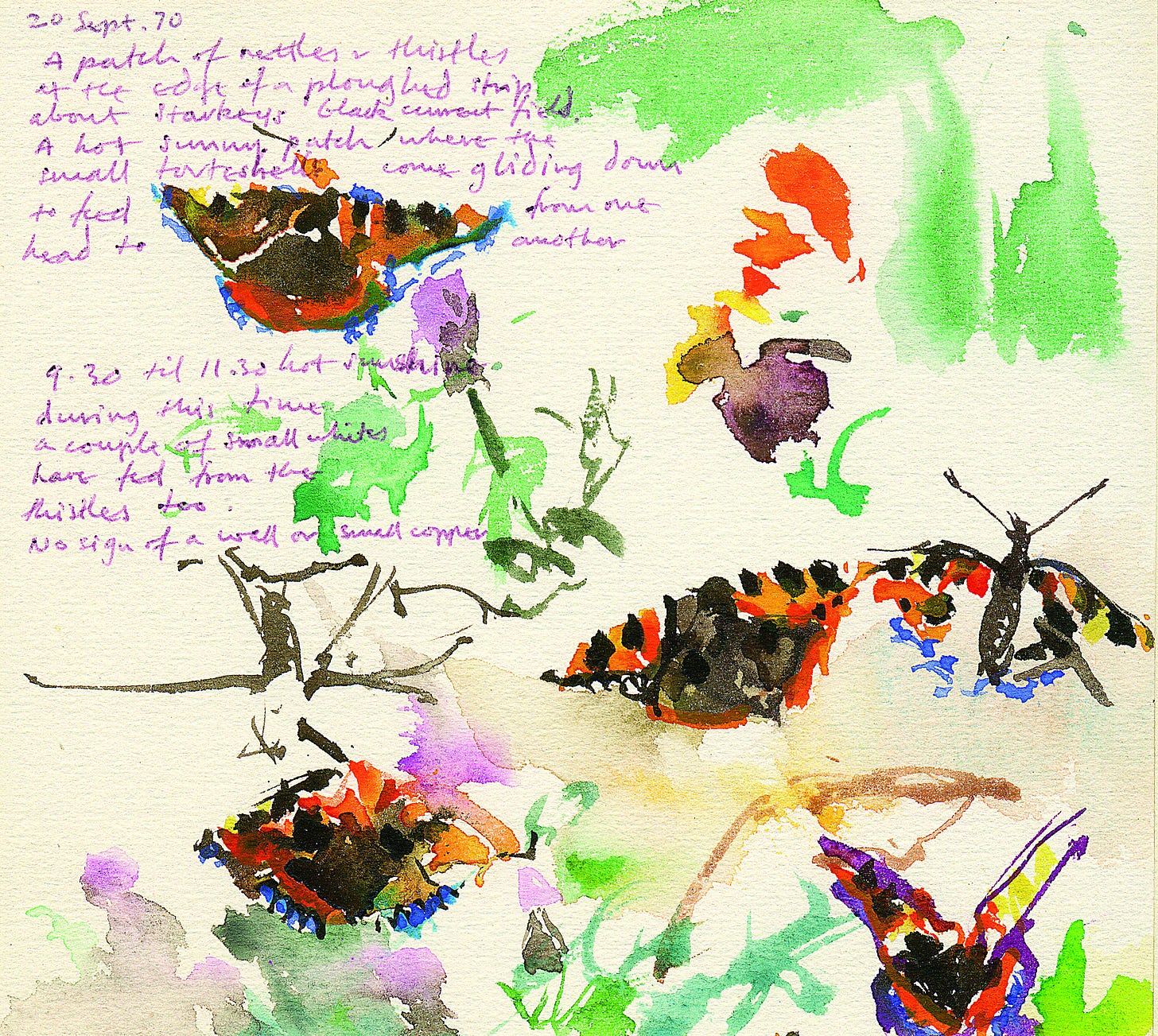

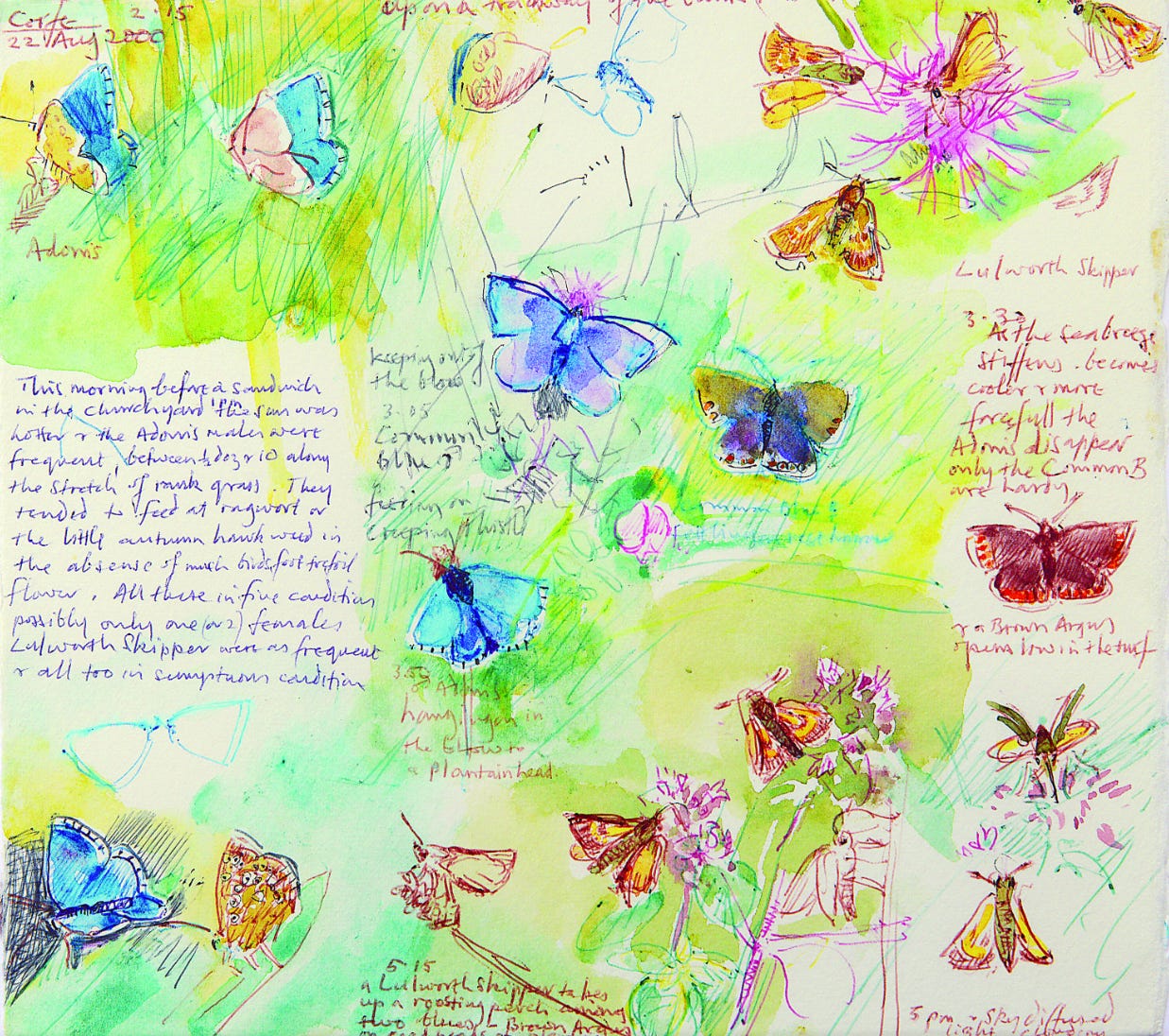

Traditionally, paintings of butterflies were based on the observations of pinned, dead specimens — faithfully rendered illustrations of flat two-dimensional, albeit colourful, laminas. David Guy Measures was anything but traditional, and he was the first artist to tackle painting and sketching these winged wonders from life, going on to portray all of the British species from his own direct observations. He was not only a superb naturalist; he pushed and extended the boundaries of the wildlife art genre.

I love these. They’re messy, unfinished, and perfectly capture the fleeting glimpse of a passing butterfly in flight. Surrounded by his field notes and observations, his work conveys that feeling of frantically noting something down before it’s forgotten; before it passes from sight and becomes a fading memory.

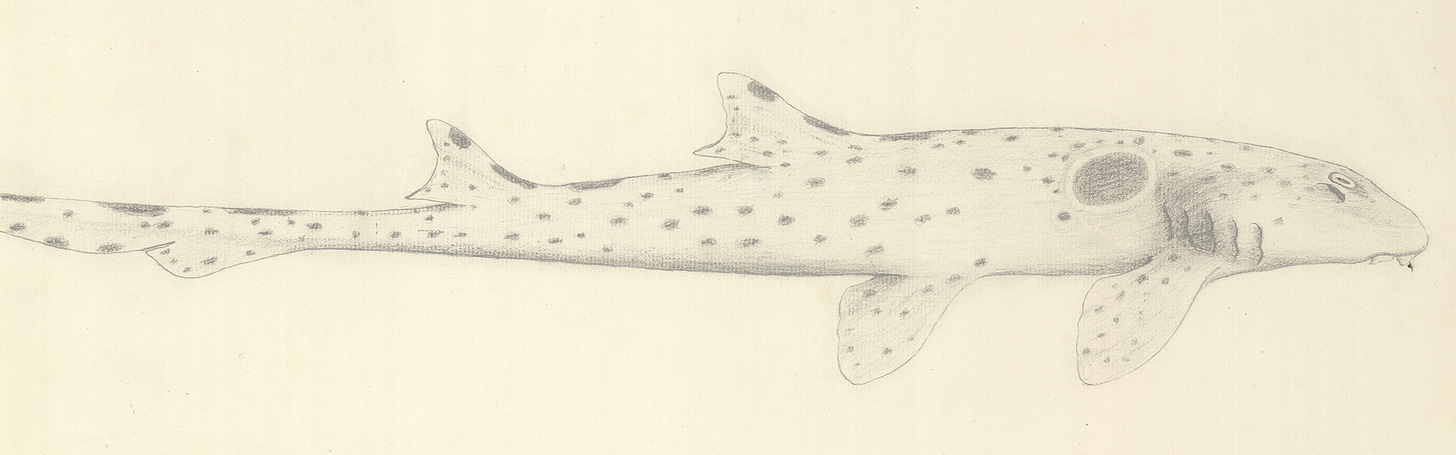

In 1768, artist Sydney Parkinson travelled with Captain James Cook on the HMS Endeavour to the Pacific, to observe the transit of Venus from Tahiti and to explore what would later be known as the east coast of Australia.

Historically, there are deep, complicated colonial connotations to these voyages. But through Parkinson’s work, we can also experience a genuine sense of wonder at what his European eyes were seeing for the first time.

With no digital camera or zoom lens, he relied on his sketchbook to record what he saw. He quickly built up an extensive body of work of flora and fauna and landscapes of Australia and New Zealand.

His sketches give me the same feeling as Measures’ butterflies - of the attempt to note down an observation before it escapes, no matter how rough. It’s the work of someone deeply passionate about discovering the world around him.

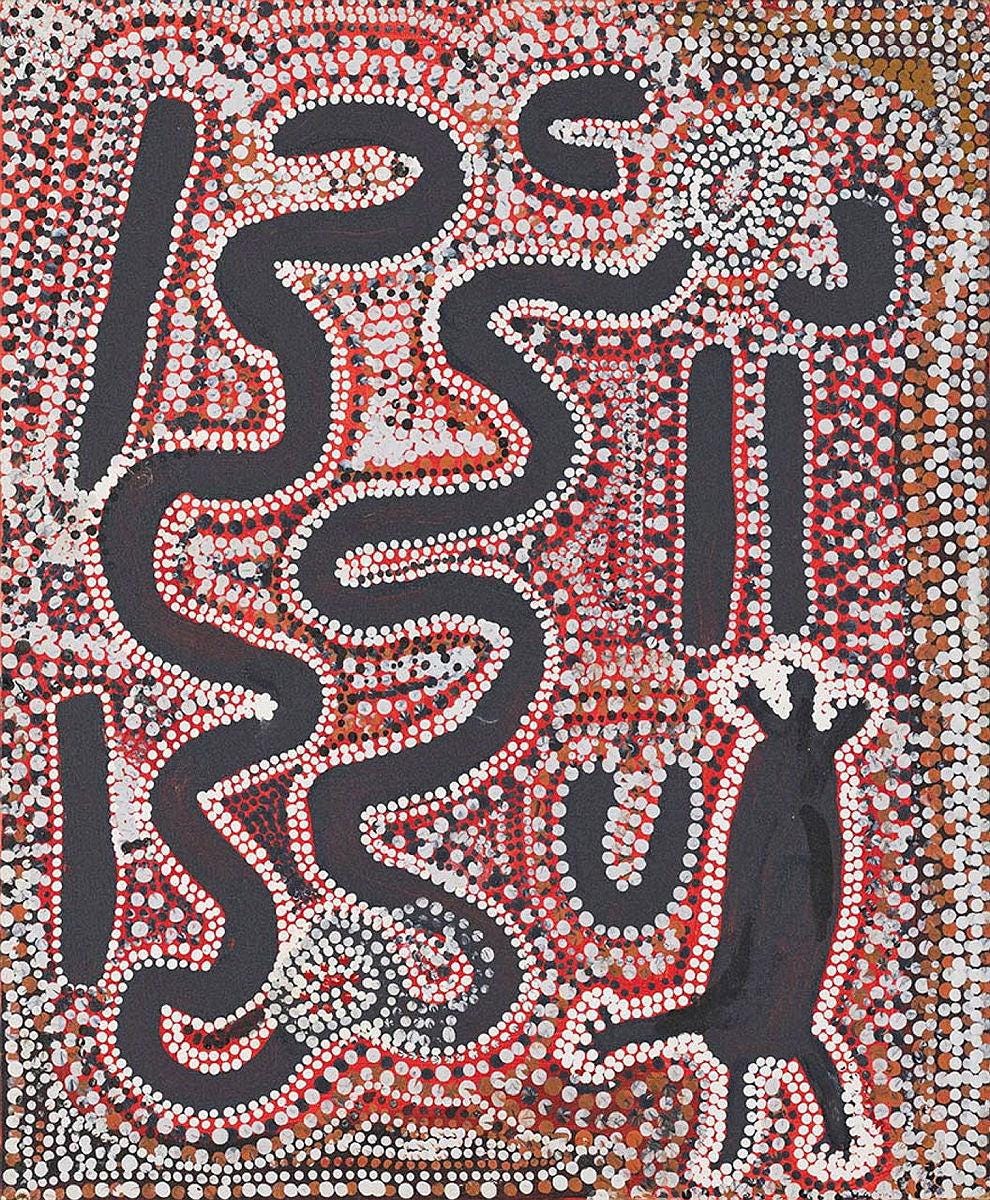

Of course, Parkinson’s experience of Australia will only ever be through the lens of someone who would never fully understand that land. The Aboriginal people have been living continuously in Australia for 50,000 years, and their culture and art is complexly intertwined with the natural world.

But in a world in which cities are expanding, nature is disappearing and connection with it is almost entirely absent from many people’s lives, can we still find inspiration from the natural world?

The Romantics like Constable and Morris longed for a return to the quiet pastoral scenes of Britain they mourned as industrialisation transformed the land. As generations of people have grown up without attachment to a place and its seasons and its native species, nature has vanished from our music, our films, our art and our design just as it has vanished from our world.

At the current rate of environmental inaction, nature’s influence on our culture will soon be in memory only - an aching longing for what we had and a realisation that we took for granted what every generation of humanity has had in abundance before us.

The next time I go out, I’ll take a sketchbook with me and do my best to capture the fleeting beauty of a butterfly on the wing, or the sparkle of the summer’s light on the down of a drake, and hold it close before it disappears.

I encourage you to do the same.

Congratulations on the shortlisting!

I’m reading GM Trevelyan’s Illustrated English Social History at the moment and I was struck by his sadness at the disconnect from nature that urbanisation brought. He mentions Bewick and the like at the end of the 18th century ‘taught their countrymen to observe and reverence the world of nature, in which it was man’s privilege to dwell’ , notes the growing popularity of landscape painting and later laments that in the 20th century urban thought and ideas ‘conquered the countryside’. Written in the 1940s I believe.

So, I came here for your post about turning unused phone boxes into greenhouses, because I make things out of salvaged and repurposed materials and I thought that was such an excellent idea, but then I read this and it really struck a cord with me! You're so right about the way that nature and art are connected, and how we humans are inspired by our environment. Thanks for the creativity fodder!