The flight of the peregrine

Blink and you miss it.

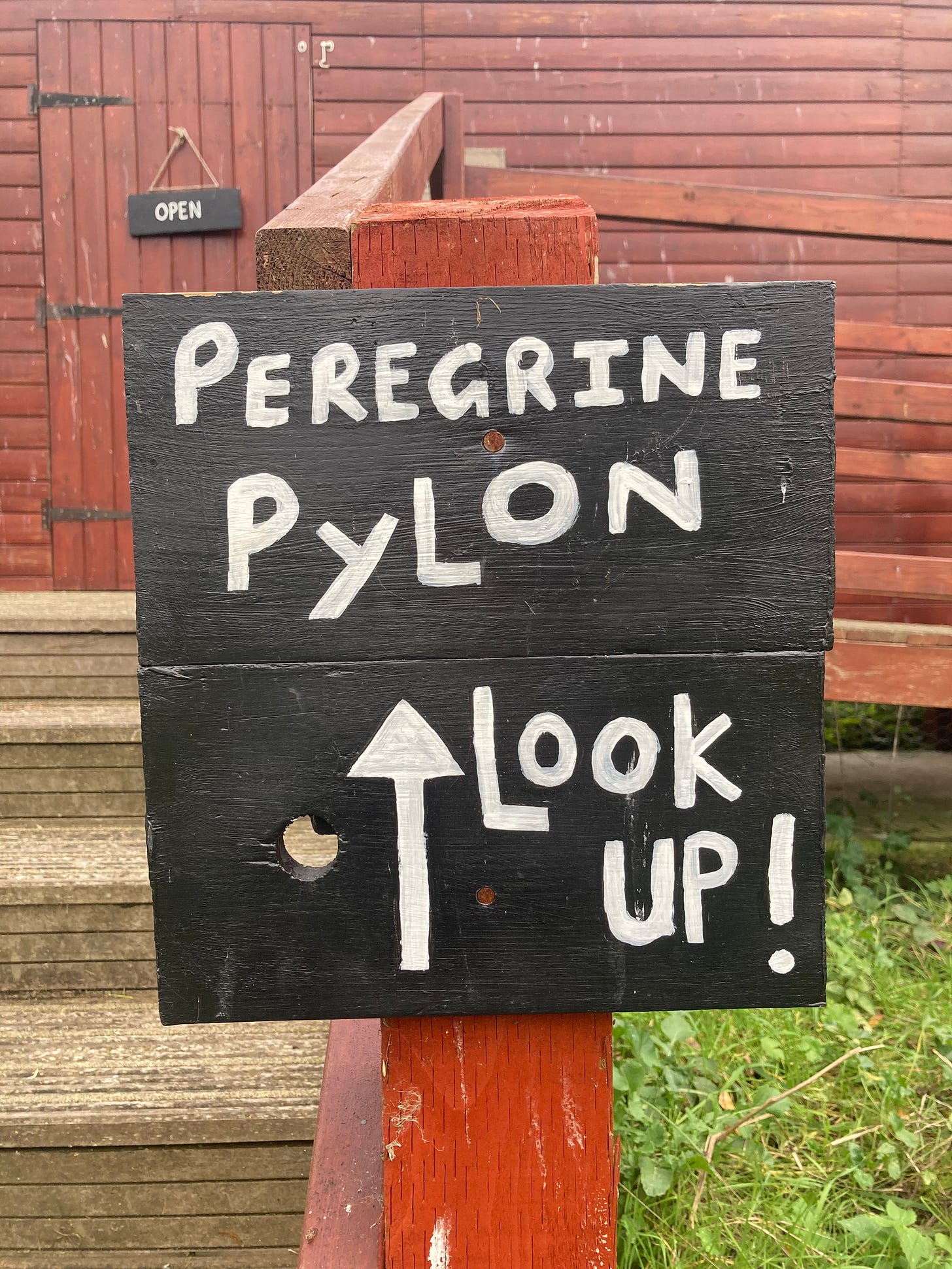

Outside the hide at the south end of Walthamstow Wetlands, you are greeted by a sign.

Obey, and there is a good chance you will see the ruler of the roost himself, the peregrine falcon, perched on a throne of grey metal.

The peregrine is an absolute machine of a bird. It’s a skillful flier, darting between London’s towers and pylons where it roosts, and dives sharply when it spots prey. And when it dives, it dives.

The peregrine has been clocked at well over 200 miles an hour, making it the fastest animal on Earth, and the force of the dive’s impact is enough to send its unsuspecting prey to pigeon heaven before it can say “coo.” There are pigeons aplenty to hunt in London, nearly three million of them, making a fine living off the detritus that humans throw away every day.

So it’s not surprising that peregrines have settled comfortably in the UK’s pigeon capital. But it hasn’t always been that way.

In the 1950s, the peregrine population had almost completely collapsed in the UK. That was largely thanks to the unfriendly pesticide DDT (a catchier name for dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) which was widely used across the country in agriculture. It did an incredible job of wiping out pests, and nearly wiped everything else out too.

As well as directly poisoning birds, it thinned the shells of their eggs, leading to high rates of offspring mortality. It also caused catastrophic damage to aquatic ecosystems when the chemical was washed into rivers and lakes from the soil, contaminating their food supply. Wildlife populations plunged.

DDT was banned in the UK in 1986 and worldwide in 2001, but our environment is still reeling from its effects today. Scientists are even beginning to join the dots with DDT and human diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Since the ban, peregrines have clawed their way from extinction and adapted well to urban life. They are a protected species which has helped them make homes in cathedrals, towers, and office blocks. But they’re not out of the woods yet. As is the same with most of the UK’s resident raptors, peregrines are relentlessly persecuted. Shooting, poisoning, trapping, and egg theft are major challenges thanks to gamekeepers going to extreme lengths to protect their profit margins.

Anywhere there is game, there will be peregrines. Such is the nature of ecosystems. But birds do not know the difference between a wild partridge and a grouse that is being reared for humans to pay to shoot. The penalty for a peregrine’s ignorance is death.

Local police authorities and divisions such as the National Wildlife Crime Unit strive to enforce the law in favour of these protected birds, but limited resources will get them only so far. RSPB’s 2021 Birdcrime report revealed that the killing of birds of prey is at a “significantly high level in England”. 2021 holds the unfortunate boast of having the second highest number of raptor persecutions in recorded history.

Earlier this year, the State of Nature report revealed the sobering statistics of continued wildlife decline in the UK. There has been “no let-up” in the loss of our plants and wildlife, and the UK is firmly one of the most nature-depleted countries on the planet. Every poisoned peregrine is a nail in nature’s coffin.

Then I walk through the wetlands near my home one morning before work. The sign bids me to look up, and who am I to refuse? My reward is the sight of a peregrine landing on the pylon, dragging a freshly caught pigeon - or maybe a gull, it’s difficult to see from this angle. It begins to pluck the pigeon-gull, diligently pulling feathers that fill the sky and spin in clouds around me, a grisly kind of snow.

For nearly half an hour I watch the bird feed, until nothing remains but a soft layer of down on the grass around my feet. It surveys the skyscrapers beyond, then vanishes.

The city is ours, but the peregrine has claimed it.