Troubled waters

Our rivers deserve better.

A few years ago I was fishing on the river Blackwater in Essex, not far from my friend’s house. The mud glistened and crackled under a glowing hot sun. My friend was finding a new spot on the other side of the marsh, when movement in the water caught my eye.

Snub-nosed, whiskered, and swimming far from shore, an animal was looking at me. As far as I knew, my friend and I were the only people on the river that morning, yet here I was eye to eye with something that could have been a beloved pet. “Whose dog is that?” I said to myself, aloud, and the creature slid down into the icy black. Just ripples remained.

I later discovered that grey seals are common along the Blackwater, although I’d never seen one that far upriver before. In fact there are seals all along the eastern coast of England, with healthy breeding populations off the North Norfolk coast a particular attraction.

The river Thames that flows through London was found to be home to 2,866 grey seals and 797 harbour seals in 2021, according to research from the Zoological Society of London. It has also been known to accommodate bottlenose dolphins and harbour porpoises, seahorses, eels, and even sharks. Today it is considered to be one of the world’s cleanest rivers running through a city.

This is an astonishing rebound after the ZSL declared the Thames as ‘biologically dead’ in 1957.

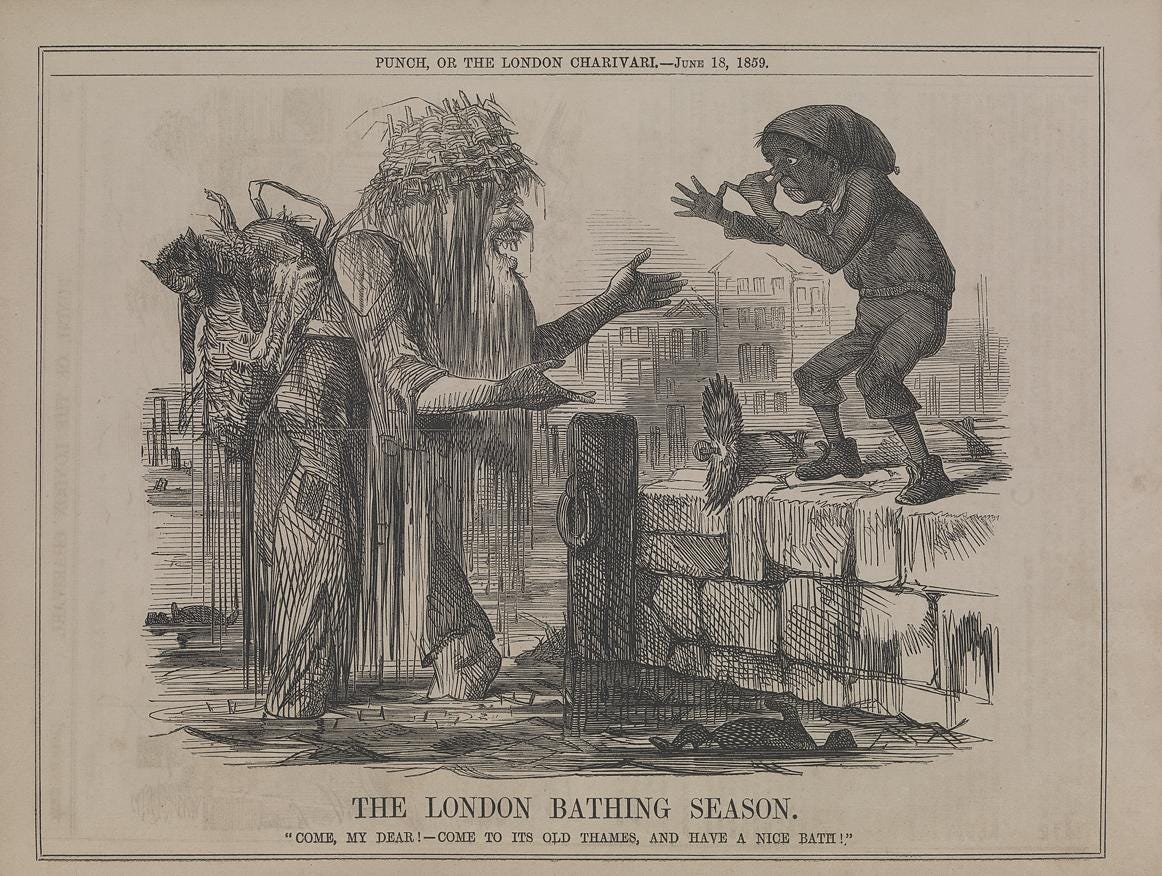

The river has a long history of being misused. In the 1850s, the river was so choked up with effluent and industrial waste people left London due to the smell, coined ‘The Great Stink’.

'Almost all living things that existed in the waters of the Thames have disappeared or been destroyed. There is a pervading apprehension of pestilence in this great city.'

When the issue was addressed, the Thames Purification bill became law in just 18 days.

The sewage system built beneath London as a result of this bill is still in use today. But that didn’t help the toxins from metal industries working their way into the watercourse, and when parts were destroyed by German bombers in the Second World War sewage began to leak again into the river.

After the ZSL’s damning 1957 report, subsequent policies strove to heal the damage caused over years of pollution, leading to the returning mammals and fish that we see today.

But there’s still a long way to go. London’s Victorian sewage system is buckling under the weight of 9 million people. Shifting rainfall patterns due to climate change are causing more flash floods, overflowing the drains to breaking point. The water is still highly contaminated with chemicals and plastics.

It’s not a unique story, either. In fact, almost all of the UK’s waterways are so polluted they are unsafe to swim in. The 2024 State of Our Rivers report from River Trust revealed that “none of England’s river stretches are in good or high overall health.”

Pesticides and nitrates from industrial agriculture run-off have a catastrophic effect on aquatic life. Freshwater vertebrate populations have declined by a whopping 84% since 1970; twice the rate of decline of biodiversity in other ecosystems.

In 2022 alone there were nearly 400,000 instances of raw, untreated sewage being discharged into the UK’s water. This kind of national negligence is a quick way to spread disease and wipe out what remains of our aquatic life.

A recent campaign drew particular attention to the Wye Valley.

The Wye is a stunning, iconicly British landscape, a postcard of emerald hills and forests threaded by a silver ribbon of river.

It’s also home to nearly 23 million chickens, the heart of Britain’s industrial poultry business. The high level of nitrogen and phosphorus in chicken manure runs off into the river when it rains, starving the water of oxygen and leading to toxic algae blooms which ravage life.

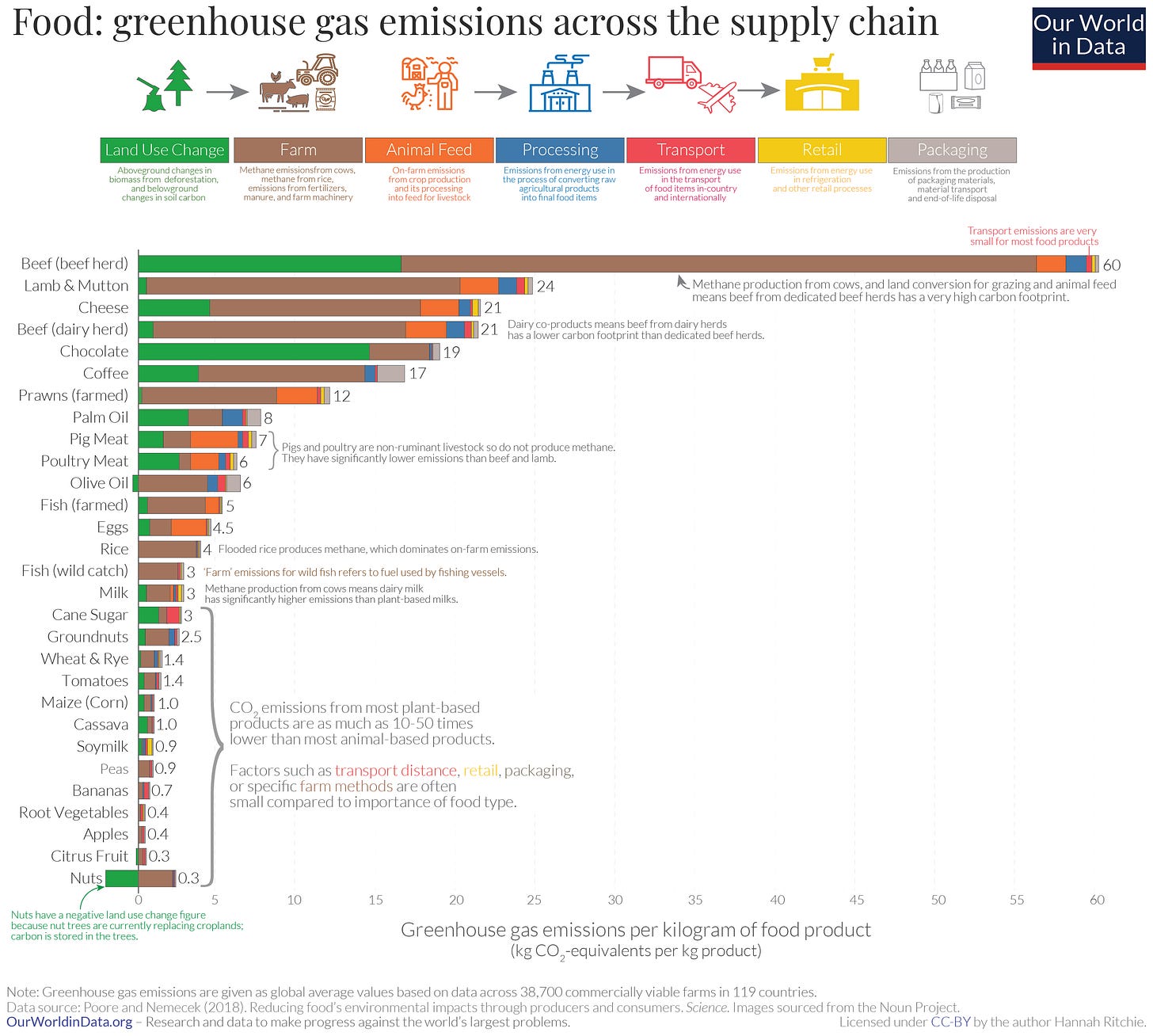

This, coupled with the deforestation associated with soy-based chicken feed and the greenhouse gas emissions emitted by the business is clear evidence that intensive animal agriculture has no role for humanity in a sustainable future.

Industrial chicken farming might be the most ethically bankrupt and environmentally destructive business in Britain today.

- The Soil Association

But local people are fighting back. The situation is so bad that thousands of people in the Wye catchment are collectively suing the poultry firms responsible for the damage.

One of the most common questions asked by people despairing at environmental degradation is “what can I do?” and the answer here is simple.

Reduce your consumption of animal and poultry products.

Landowners must step up the green infrastructure required to limit the use of toxic chemicals, bind the soil and reduce surface water run-off, but the diet choice is all ours.

It is only through collective action that we can influence real change, so vote with your voice and with your wallet, and send a clear signal that your trust as a consumer no longer lies with firms that destroy the natural beauty of our country.

For more detail on how to protect our rivers, see:

Reduce the climate impacts of the food you eat: