We need to rethink our relationship with water.

Not in the future. Today.

It rained yesterday.

In Essex, where I’m spending a couple of days, there was a sprinkling of rain for a couple of hours. I hear in London there was a bit more. I hope there was. It’s the first time I’ve seen rain in well over a month. Maybe even two.

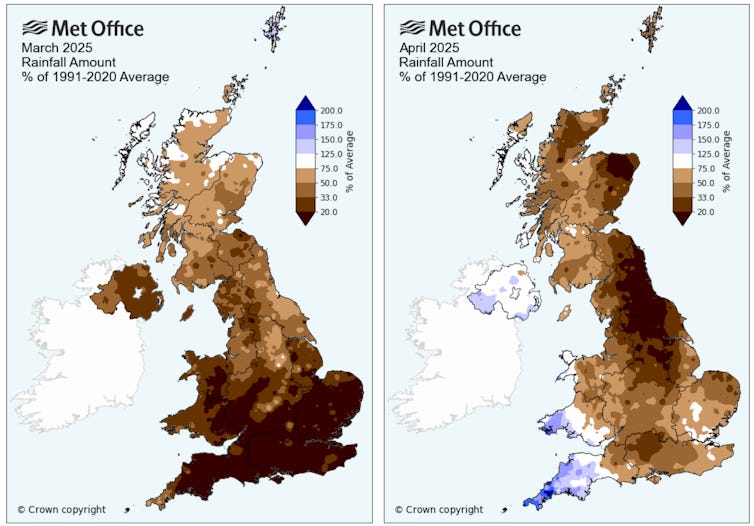

This spring is on track to be - if it isn’t already - the driest ever recorded in the UK.

The springs of my childhood were beautiful: sunny and fresh, with rain sweeping the land and lush green vegetation bursting into life.

This spring has been almost entirely without rain. Temperatures we’d expect to see mid-summer have risen in April instead. Soil is rock hard and cracked, plants and grass are dusty and browning, and rivers are low and quiet. Record wildfires have spread throughout the country.

Drought experts have met to discuss measures after reservoirs have shrunk, and more than one farmer has voiced alarm at the drought. "If rain doesn't come soon my crops won't recover,” says one. We can expect to see food prices skyrocket this year.

We’ve moved very quickly from being warned of the potential impacts of climate change to feeling them firsthand.

But for those of us brought up in a culture of abundance and consumption, the alternatives are difficult to imagine. The recent rain is nowhere near enough to fill up the reservoirs and water the crops. We can hope that ‘normal’ weather patterns will return but as long as emissions continue to rise and we continue to treat natural resources as if they’re infinite, things will only get worse.

Agriculture isn’t the only industry in need of fresh water. Microchip production for electronics, for example, requires a continuous supply of pure water. Drought restricts the production of microchips, which restricts the production of electronics, which disrupts supply chains and economies around the world. In 2022, the water levels of the Rhine in Germany were so low that shipping routes were affected. These are just some of the tangible economic costs of climate change.

When water does come, the ground will be so hard that we’re likely to see considerable flash flooding. This is how climate change manifests through water: either too little, or too much.

In 2021, Cape Town became the first global city to come close to running out of water. One of the more drastic water-saving measures implemented was the felling of non-indigenous trees to protect reservoirs.

Alongside dramatic emissions reductions to try and mitigate even worse outcomes of droughts, we need to completely reimagine our relationship with water.

A phrase I’ve often heard throughout my life - particularly at school when comparing the UK with countries around the world - is that the water we use to flush our toilets is cleaner than the drinking water of other places.

I don’t know about you but I always thought this was a strange boast. It didn’t make sense to me that we would flush our toilets with drinking water. But then seemingly infinite fresh water always came out of the tap so who was I to argue?

Using a single water supply for everything is certainly more cost-effective than using potable water for some taps and grey water for others. But our water systems were built with the short-sightedness that there would always be an abundance of fresh water on hand. That is no longer the case.

Grey water is the dirty water that is left over after washing the dishes or taking a bath. At the moment, that water is immediately drained into the sewers. A vision of a more sustainable society would be to put that water to better use.

The impact of drought is felt not just in industry but in the natural world, too. It reduces the amount of nectar produced by flowering plants, which negatively impacts pollinating insects. So if there’s one thing you can actively do to support bees and plants and trees, it’s give them some grey water.

Collect your washing up water in a bowl. Shower with the plug in. Water the soil with what’s left over. Soil and compost are good at filtering out contaminants so you don’t need to worry about getting some diluted shampoo on your rose beds. Mild soap detergents won’t affect plants - just don’t go dumping a load of bleach and harmful chemicals on them. Don’t use it on edible crops, either, as the bacteria and contaminants of untreated grey water can spread disease.

If you’re not sure about the chemicals in your grey water then consider how long you have to leave the tap running while you’re waiting for it to heat up. That’s litres of potable water going directly from the system to the drain. It’s a complete waste. So collect it and do something useful with it.

You don’t even need to have a garden to make use of it. I live in a flat, and the lavender growing by the street downstairs is stunted and withering in the lack of rain. But lavender is a valuable food source for bees of all types in the summer, so I lug my washing up bowl down three flights of stairs and give it to the plants. I do it at night so that 1) the sun doesn't immediately dry it out and the water has time to filter into the soil, and 2) my neighbours don’t think I’m a nutter.

Then again, what’s more sensible behaviour? Giving plants clean water we could be using for drinking? Or giving plants water we can’t do anything else with?

Imagine if a grey water treatment system was installed in every neighbourhood or even every house, filtering the worst of the contaminants to reuse in different places. This would help alleviate the pressures on the reservoirs.

Permaculturists have adopted the recycling of grey water through reedbeds. By filtering water from showers and dishwashers through layers of gravel and sand and then through reeds, the water goes back into the landscape in the form of a pond which supports a wider ecosystem. Nature is well adapted to filtering out contaminants so clean water can then be redistributed to vegetable gardens.

That’s just common sense.

Changing our relationship to water in a changing climate will require the same shifting cultural mindset we need to apply to everything. It can be summed up in two words:

Don’t waste.

We can no longer afford to extract what we can’t put back.

Installing grey water treatment and water recycling systems in every household is likely to be, well, expensive. But my counter to that would be to consider the alternative. When months of brutal drought grip our formerly rainy isle in the summers to come, what will the cost be?

Hundreds of millions of water are wasted every day through leaking infrastructure. Untreated sewage is continuously released into rivers and seas. Yet the bosses of water firms still walk away with millions of pounds in bonuses every year.

What’s the cost of not upgrading our water infrastructure?

What’s the cost of not changing our attitudes to water?

What’s the cost of not doing anything?

There will come a time very soon when we will be clinging on to every drop of water we can.

Adapting to that world begins today.

100%, Tom, and something I’ve been doing for years (washing my veg in a bowl and then using that water for something else etc). But it’s the systems change to grey water use as a rule that will make a difference.

Another much overlooked but horrifying use of water is AI. Just had a long discussion with colleagues about that.

I agree. I live on the Suffolk coast and it didn't rain yesterday and hasn't rained for weeks. It is terrible to see the state of the countryside with the grass all brown and crispy and the earth so dry it looks like sand. I have water butts in the garden but the stored water doesn't last long and I am desperate to keep my garden alive for the wildlife. April showers and the vibrancy of spring seem to be a distant memory.