Are we alone in the universe?

The answer is closer than you think.

Something is out there.

Sailing the deep infinite, riding unimaginable waves of dust and radiation and nothing, is an object about the size of a small car. It has no particular destination in mind, and is in no particular hurry. It is content to just travel, and has been doing so for 47 years.

Its name is Voyager 1, and it is, at the time of writing, about 24.8 billion kilometres away. It is the furthest man-made object from Earth. There is a very good chance it always will be. It will never return.

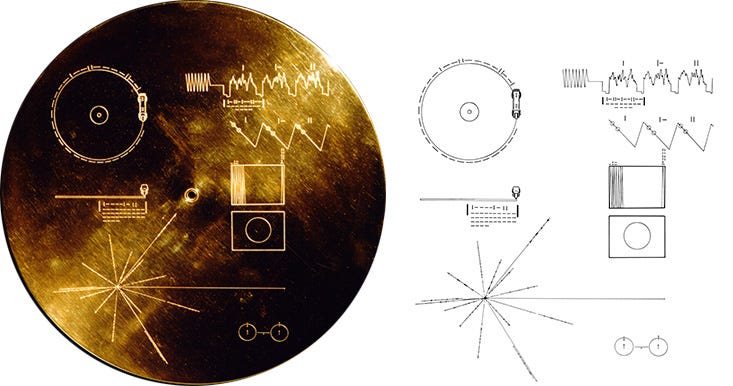

On board Voyager 1 is a golden disc. If somebody, or something, were to ever intercept its interstellar journey, they would find a diagram on this disc alongside instructions written in binary arithmetic.

If they were to follow the instructions, they would likely be the first extraterrestrial beings to ever hear the sounds of planet Earth. Or at least, the sounds of Earth from 19771.

They would hear greetings in 59 human languages. They would hear laughter, music, the sounds of tools and footsteps and traffic. They would hear thunder, waves, crickets, frogs, a dog barking. They would hear whale song.

They would be listening to a time capsule, an immortal emissary of life on a little planet in a small galaxy, a gentle hand reaching out across the cosmos to say, “we are here. Is there anyone else out there?”

Ever since humanity first looked up at the stars, it has wondered what could be out there. Are there thriving civilisations on planets like our own, looking back at us? Or are we destined to ride out the mysteries of the universe alone?

Stories of beings other than humans have pervaded our culture since we first gathered around campfires. They are the mythologies we told ourselves, the folk tales we bonded over. Religion helped us make sense of the world, from Islam and Hinduism to the Aboriginal Dreamtime. But in 450 BC it was the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras who suggested the moon might not actually be a god after all, but a rocky planet a bit like our own.2 Not only that, but it might even harbour biological life. He was exiled for his claims.

Theories of the universe have clashed with that of religion for hundreds of years. In the 16th century, Copernicus’s groundbreaking suggestion that the Sun, not the Earth, lies at the centre of the universe ruffled more than a few feathers - although he was adamant it did not contradict the Bible.

Despite the insistence of religion about the centrality of mankind to God’s plans, generations of astronomers began to peel away the mysteries of what lie beyond Earth’s atmosphere. As they have done so, the idea that there might be life out there has pervaded the cultural consciousness.

The Italian astronomer Schiaparelli described in 1877 what looked like long, straight lines on the surface on Mars. The American astronomer Percival Lowell, with a series of three books, then championed the belief that these were canals, the engineering of an industrial, intelligent civilisation designed to transport water from the ice caps to the drier equator.3 This captured the world’s imaginations.

In 1895, H.G. Wells published The War of the Worlds. The novel depicted a malicious extraterrestrial race invading Earth, and is regarded as one of the first instances of science fiction.

Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

- H. G. Wells, The War of the Worlds

Today, you can barely switch on the TV, go to the cinema, or walk into a bookshop without diving into richly imagined worlds from far distant solar systems. Many of the biggest earning entertainment franchises of all time have tapped into our fascination with what lies beyond our own planet.

A practical, meaningful search for extraterrestrial intelligence began in the 1980s with the launch of the SETI (Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence) Institute in California, USA. Much of the work focuses on surveying the universe through telescopes - on the ground and in orbit - and research by over 100 scientists. The surveys are based on the search for signals and patterns in the electromagnetic spectrum amidst the background noise of the universe.

In 2015, Stephen Hawking and billionaire Yuri Milner set up $100 million project Breakthrough Listen, based at the SETI laboratory, as the largest comprehensive search for intelligent life to date. The project uses “some of the world’s largest and most advanced telescopes, across five continents, to survey targets including one million nearby stars, the entire galactic plane and 100 nearby galaxies at a wide range of radio and optical frequency bands.”4

We, as a society, have been making a heck of a lot of noise for decades now. Radio and television signals have been firing off into space at all angles, some intentionally, most unintentionally. Despite the depictions in many of our favourite stories of aliens as being antagonistic, we are desperate for someone to pick up the phone.

The universe is old. Extremely old. And extremely big. In 1950, the physicist Enrico Fermi considered that there is a high probability that some of the billions of Sun-like stars in the Milky Way alone likely have planets in habitable zones, and many may have developed intelligent life long ago. And since these stars are much older than the Sun, the Earth should already have been visited at the very least by their probes. In 1992, scientists confirmed the discovery of the first planet outside of our solar system - an exoplanet. As of July 24, 2024, there are 7,026 confirmed exoplanets, with around 16 in habitable zones.

When these figures are calculated, it’s a mathematical certainty that life is everywhere, and we should have discovered it by now. But to date, no evidence of life beyond Earth has ever been found.

So Fermi questioned, in what became known as the Fermi Paradox, “where is everybody?”

There have been many attempts to explain the Fermi paradox. Some are as entertaining as our favourite works of science fiction, like the idea that there is a super-advanced predator civilisation travelling the universe and the smaller ones have the common sense to not loudly broadcast their location. Unlike us.

Others are more convincing, like the idea that perhaps simple life is abundant in the universe, but advanced life capable of space travel is not. Or humanity is in such a remote part of the universe that we’re akin to modern day uncontacted tribes in the Amazon.

Or perhaps, most likely, a civilisation is incapable of growing to the point at which long-distance manned spaceflight is possible, let alone sustainable, before it destroys itself. Theorists call this the Great Filter - the moment at which physics prevents a civilisation from getting too big for its boots.

Consider the seemingly empty void of the universe. Now look out of the window. Look at the trees, the birds, the grass, the flowers in your garden, the food on your plate.

For many years, scientists have attempted to estimate the number of species living on Earth. The numbers have varied wildly from a few million to a few trillion. A 2011 study by Dr Camilo Mora determined around 8.7 million species, give or take 1 or 2 million. More importantly, 86% of all species on land and 91% in the seas have yet to be discovered, described and catalogued.5

And yes, you read that right. Nearly every species currently on the planet, nearly every thread in the rich tapestry of life on Earth, is yet to be discovered. We know more about the surface of Mars and Earth’s moon than we do about our own oceans6.

That study was released 13 years ago. But since 1977, the year Voyager 1 departed Earth on its cosmic journey with its record of frogs and crickets and whale song, global biological diversity has plummeted by 73% at our hands. The 2024 Living Planet Report7 paints a picture of a once vibrant planet now fished, mined, deforested and polluted to a shadow of its former self.

The rapid expansion of industrial human civilisation is accompanied hand in hand by a catastrophic loss of nature. The natural systems that have enabled life to flourish over millions of years - the systems on which we rely every day for our food, water, and a stable climate, are at risk of swift, irreversible and catastrophic collapse in just a handful of years.

Early warning signs from monitoring and scientific evidence show that five global tipping points are fast approaching. Each tipping point poses grave threats to humanity, Earth’s life-support systems, and societies everywhere.

- Living Planet Report, WWF, 2024

This is far from science fiction. This is the hardness of reality - of the unstoppable force of humanity colliding with the immovable object of physics.

In our obsession with unravelling the mysteries of what lies unreachable distances away, we have abandoned attention to the ground beneath our feet, to the soil and the water and the air from which everything we have ever known and ever loved has sprung.

Scientists have been warning about this for decades now. They have been almost entirely ignored. We can blame our political and business leaders - the ones who wield the most influence and ability to shape the world - for a complete failure to do anything. But it’s difficult to contend with the fact that, armed with all the knowledge we have about our situation, 77 million people just very deliberately voted for a president who is entirely open about his plan to dismantle any and every form of environmental, pollution and climate-related regulation he can get his hands on and ‘drill, baby, drill,’ consequences be damned.

As we pontificate about why the silence of the universe is deafening, we stand with our toes over the edge of a crumbling cliff, and lean forwards.

The search for life other than our own has focused on a key word - ‘intelligent’. Someone or something we can shake hands - or tentacles - with, look into the eye and connect with. But our lives, if we let them, can be filled with connection. With each other, with our world, with any of the 8.7 million species we share it with.

Prince William was described by The Times as making a ‘bizarre admission’ for taking comfort and peace from lying beside his horse and listening to it breathe.8 But anyone who has spent time in the company of animals will be familiar with that feeling, that warmth that rises up from somewhere within our spirit that can only come with the mutual respect and trust of a creature of another species.

One of my favourite photographs is of this gravestone that is regularly shared around the internet. It shows a deep, aching compassion for non-human life, a bond that many of us spend our entire lives searching for.

In 1990, six billion kilometres from Earth, Voyager 1 looked back and took a photo that came to be known as the Pale Blue Dot. It shows the only home that humanity has ever known - the only world we know of in the universe capable of supporting life - as a mere pinprick in the vastness of space.

If there is life elsewhere in the universe, there is a good chance we will never find it. But there is also a chance that we share a planet with the only life that has ever and will ever exist in the universe. In the infinite spread of nothingness, this blue orb just a few thousand miles wide might be a mathematically impossible miracle, a speck of unbelievable dust drifting on the currents of chaos.

We live in a moment of time unparalleled in the entire history of the human race. We are the last people - the only people - who have an opportunity to pull ourselves back from the brink of oblivion. To reshape our society in a way that works for every species on Earth, not just for a handful of billionaires. To clean our water and heal our soil and ensure the sounds of frogs, crickets and whales are heard where they belong, not only on an inanimate object billions of kilometres away.

As we stand eye to eye with the Great Filter, I choose to believe our future is in our hands - not that of the universe. Because the truth is, we are not alone. We have each other, and this little ball of rock and water and the improbability of life we call home. It’s up to us - and only us - what we do with it.

One clear morning, on April 12th 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human being in space. As he broke through the atmosphere and the dizzying sprawl of infinity was revealed to him, he turned around and looked down on everything he had ever known.

“I see the Earth,” he said. “It is blue. It is amazing.”

Loved this piece. Your writing has always been good, but your blogs just keep getting better.

What a wonderful yet disturbing article. It has always saddened me that most of us are so self absorbed that we fail to appreciate all of the wonders of nature around us. The numbers of undiscovered species is truly mind boggling. Thank you for writing.